Unfortunately, such threats, repeated over the last three decades, did not deter the government from constructing the dam. And this was despite a report of a team of experts from the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF) exposing how the project had disregarded several ecological factors. The fight is now against corruption in compensation for the displaced and increasing the dam’s height. A number of rallies, dharnas, indefinite fasts, agitations, public meetings and padyatras have been held during this period even as the government tried to hush up the matter.

The movement has had its share of victories. Owing to it, rehabilitation of the displaced prior to launching such projects has become a subject of debate. Other social effects of the projects have also been highlighted by the movement. Its greatest achievement is that it questioned the environmental and current development model at an intellectual level and brought it to the international forum for discussion.

Under the Narmada Valley Development Project, 30 major and 135 medium sizeddams were planned on the river, which included giant projects such as the Sardar Sarovar and Maheswar dams. In 1985, the World Bank announced a loan of $450 million for the project. Four years later, the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA) erupted in the form of a mass movement. It brought the project under the scanner and demanded reconsideration.

Over 30 years, the movement, along with rehabilitation and resettlement issues, it has continued to raise several other environmental and biological concerns about factors affecting public health.

In 1994, a World Bank expert team conducted a survey of the Narmada Valley and reported several irregularities. It found that the impact of the project on the environment had not been properly assessed. Moreover, it said, displacement and rehabilitation could not be efficiently carried out with the existing methods. As a result, the World Bank withdrew the loan. This was a major victory for the movement. The Union government, however, went ahead with the original plan of dam construction despite the C also raising environmental concerns.

The Sardar Sarovar project was completed in December 2006 and inaugurated byNarendra Modi, then Gujarat chief minister.

The NBA claims that the project affected nearly 3,20,000 lives. The submergence area of Indira Sagar dam covered 255 villages, including the 700-year-old districtof Harsud near Khandwa in Madhya Pradesh. Harsud was feared to be submerged during the monsoon of 2004. Therefore, the village was evacuated on 30 June without prior rehabilitation of the displaced.

Hundreds of activists from across the country — human rights crusaders,environmentalists, writers, intellectuals, film and media personalities, students, women, tribals, farmers and many others — have joined the Narmada Bachao Andolan. Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, who is also part of the movement, debated the issue in depth in her book The Cost of Living. In 2006, Aamir Khan lent support to Medha Patkar in her struggle for rehabilitation and resettlement of the project-affected. He personally went to meet the activists, after which he was widely criticised. Gujarat even imposed a state-wide ban on his film Fanaa.

Despite differences, the movement’s leadership has never resorted to petty politics or indulged in a blame game. They treat different approaches with respect and call it a division of labour.

Stellar Achievements

How far has the movement succeeded in achieving its goals? And though the demands have been toned down over the decades, can the issue be trivialised?

Rehmat, a member of Manthan Adhyayan Kendra, a research organisation monitoring water and energy issues in Madhya Pradesh, has been part of theNarmada Bachao Andolan for the past 11 years and has been personally affected by the project. He says, “In totality, an evaluation would reveal that even though the construction of the dam could not be stopped, the movement has had a comprehensive impact. It is no longer easy to forcefully evict people from their land. Prior to NBA, there was no policy for land compensation. The extent of insensitivity was such that when the issue of rehabilitation was raised by NBA, the government did not even have the figures for people affected by the project. The movement forced the government to offer land as compensation to people displaced by the Sardar Sarovar project, though several lacunae remain. The Andolan has had a larger impact as it created awareness about several other issues. People have learnt to fight for their rights.”

Abdul Jabbar, who has been a crusader for the Bhopal Gas Tragedy victims for decades, shares Rehmat’s views. “The dam was built but it has opened debates surrounding other such projects. The harm of such giant projects has become a subject of debate internationally. It is a major achievement. People in hundreds of villages now know the importance of a movement and how to stand up for their rights even if it means fighting the system,” he says.

“The movement has united activists across the country and inspired other movements,” says Shankar Tadwale, convener of Khedut Mazdoor Chetna Sangathan. “It brought the tragedy of displaced lives to the country’s notice and forced the governments to change their attitude towards rehabilitation.”

Former chief secretary of Madhya Pradesh, Sharad Chandra Behar, who has also been part of the nba says, “The movement that raised its voice against the so-called model of development is the first example that shows how to protest against such major projects which were earlier accepted without question.

The NBA has created awareness about the widespread harm of such projects not restricted to the people of the affected area but on a wider canvas. It changes the land, its flora and fauna, its environment, its culture as well as its history. It has brought issues of human, social, cultural and environmental impact of such projects into popular discourse. Thanks to NBA, protests against nuclear and mining projects have also been launched. The international community acknowledged it when Medha Patkar was appointed as a member of the World Commission on Dams.”

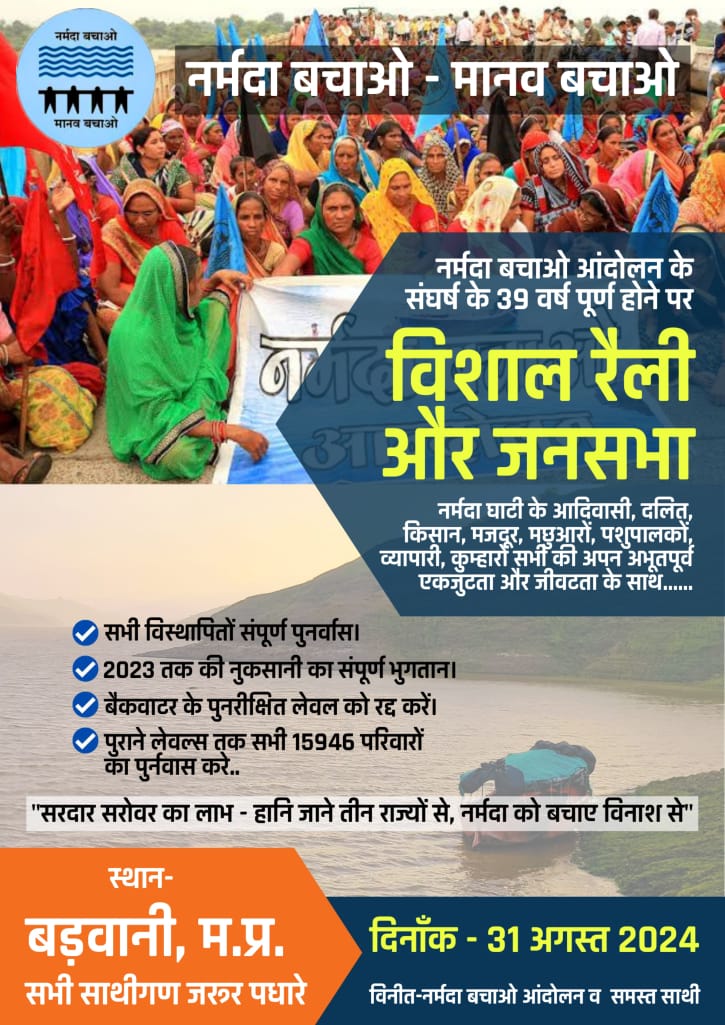

Drowing in sorrows Villagers spent days immersed in water as a form of protest against the dam

Dam(n)ed by the State

Quoting Jawaharlal Nehru when he spoke to the villagers who were to be displaced by the Hirakud dam in 1948,Arundhati Roy begins her essay ‘The Greater Common Good’ thus: “If you are to suffer, you should suffer in the interest of the country”. In the context of expensive projects, governments continue to function under this impression of serving the ‘greater common good’. In fact, they have gone a step further by alleging that such movements are a hurdle in the path of development. For instance, recently a group of farmers protested against the increase of water level in the Omkareswar dam in Khandwa region by standing in waistdeep waters for over a month. Madhya Pradesh cm Shivraj Singh Chouhan accused the protest of being “anti-development” since the project would benefit the whole country.

According to Rehmat, the government has not meted out such autocratic treatment to NBA alone. It has, in fact, been equally insensitive in other matters like land acquisition. Despite knowing how the land bill in its present form curtails farmers’ rights, the State ignored all the protests and agitations against it. The Modi government’s keenness to pass the bill is “very disturbing”. On the one hand, governments are doling out land and other facilities to industrialists for free by organising investor meets. On the other hand, farmers are protesting non-violently, sticking to the principles of satyagraha. But no one is ready to listen to them.

“It has become a one-sided affair now,” says Tadwale. “Governments no longer heed mass movements. Activists are labelled anti-development, anti-national and even Naxalites.” Explaining the reason behind this, he says, “There is a section which wants to monopolise and control all the resources in the country to exploit it for their own profit.”

“The government and the administration firmly believe that if some of the people have to sacrifice for the development of the country, it is justified,” says Behar. “Politicians also tend to believe that such movements have no constitutionallegitimacy since they are the real public representatives.” Sharing one of his experiences, he says, “While I was part of the administration I often heard politicians say that they knew what people really want better than the activists.”

Democracy beyond elections

The political nature of mass movements has long been debated and there are several opinions surrounding it. While some prefer to believe that they are social movements devoid of politics, others hold that the issues raised by them arepolitically motivated. A third section has a contrary view, claiming that they have an active engagement in politics. The emergence of Aam Aadmi Party (aap) on the political scene sparked off the debate strongly. Later, several activists who were earlier part of the Narmada Bachao Andolan joined aap and contested elections. Alok Agarwal is one such member of aap who is now the convener of the party’s Madhya Pradesh unit.

“There has always been confusion about politics and electoral politics,” says Rehmat. “Earlier people involved in mainstream politics used to accuse us of playing politics in the guise of mass movements — to which we replied that we were not indulging in party politics,” Rehmat recalls. This caused further confusion. In 1995-96, it began to emerge that for meeting their objectives, social movements are needed to participate in electoral politics. However, electoral politics is typically exercised on the cards of caste and community appeasement, money and mafia. The popularity of Anna Hazare and the rise of AAP made clean politics seem possible and the 2014 Lok Sabha election saw several activists entering the fray.

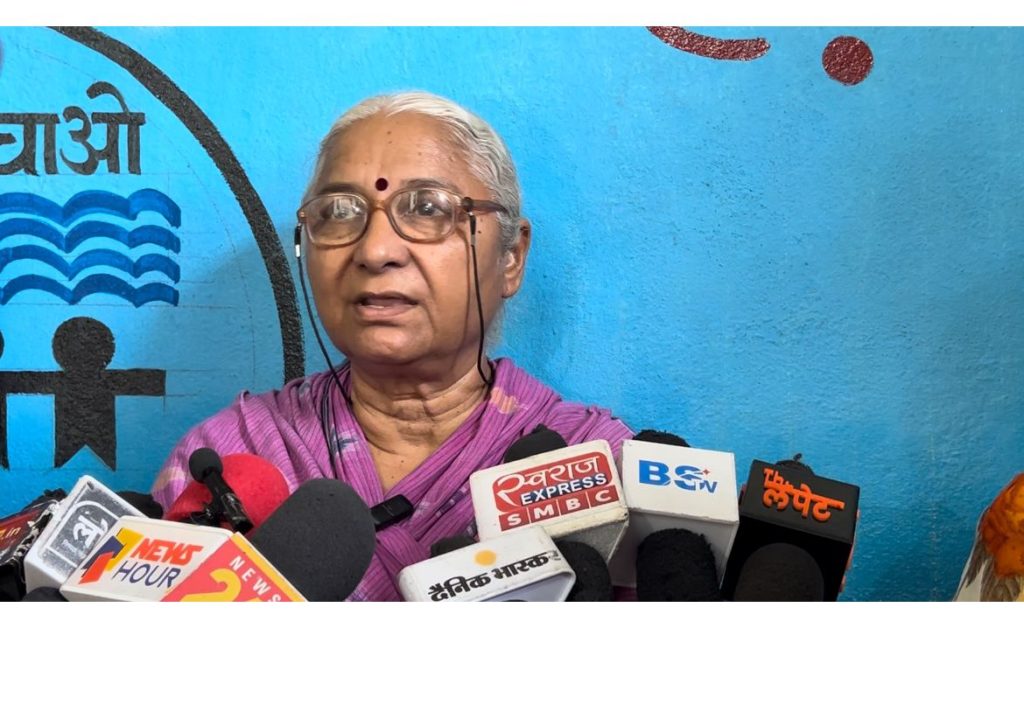

Inspiring figure Medha Patkar has been steering the movement, directing its flow since inception

Sharad Chandra Behar has a more nuanced perspective. He says, “The state is part of society and politics is one of its aspects. But in the contemporary dialogue, politics is seen as something distinct. By referring to them as ‘social’, an illusion is created that mass movements raise nonpolitical issues.

After AAP’s rise to power, the central government probably felt that if it gives in to activists’ demands, it will give the AAP an edge. So, they started weaving another narrative of how an association with politics has rendered the morality of such movements questionable. We need to understand that NBA is not a social movement but a non-electoral political issue. It is important to know the difference.”

“There is nothing wrong with leaders of mass movements entering electoral politics,” points out Abdul Jabbar. “But it requires a lot of preparation and patience.”

What lies ahead

On 28 July, a conference was held at the Constitution Club of Delhi to celebrate 30 years of Narmada Bachao Andolan in which its struggles, challenges and the way forward were discussed. The NBA held a padyatra in the Narmada Valley started from Khal Ghat on 6 August and ended in Raj Ghat on 12 August.

Meanwhile, an independent six-member team submitted its report after carrying out a survey of villages affected by the Sardar Sarovar project in May. The report, Destroying a Civilisation, reveals that thousands of displaced families still await rehabilitation while many living in the submergence zone have not even been counted in the project-affected list, thus being excluded from any possibility of compensation and rehabilitation. If the height is increased any further, more villages will fall in the submergence zone, affecting thousands more.

The movement began three decades ago with the slogan, “We will drown but we won’t move” but could not prevent the construction of the dam. And eventually, the demands were scaled down several notches. “In the present scenario, the bigger question should be how to make our governments more reflective of the people.” Quoting Plato he says, “As long as power is in the hands of a few, there will be no real democracy. This is why all movements must strive for real democratisation while upholding their identity and objectives. If the current trend of governance continues, demands will remain unheeded and curbed.”

In all of this, the strength and commitment towards the movement displayed by the people of the Narmada Valley so nonviolently has been absolutely commendable. And they continue to inspire many others in similar plights.

Chronology of the Resistance – The NBA Timeline

18 August 1988

Narmada Dharangrasta Samiti of Maharashtra, Narmada Ghati Navnirman Samiti of Madhya Pradesh, and the Narmada Asargrasta Sangharsha Samiti of Gujarat had come together in opposition of the dam which led to the formation of the anti-dam campaign known as the Narmada Bachao Andolan in 1989.

28 August 1989

MP framed a rehabilitation and resettlement policy which promised five acres of fertile, irrigated land to the displaced along with land for housing at the site furnished with necessary resources.

28 September 1999

A historic rally was held at Harsud on 28 September 1989 in which over 50,000 people from different parts of India participated to protest against the project.

9 August 1991

In BD Sharma vs Union of India, the Supreme Court ruled that rehabilitation of the displaced should be complete within six months.

Forward march Earthy slogans raised by farmers under the NBA’s banner brought awareness of the basic issues

18 June 1992

The Independent Review Commission appointed by the World Bank, the MorseCommittee, recommended the Bank to pull out of the project.

26 June 1992

The Narmada International Human Rights Panel supported by 16 countries and 42 organisations released its report.

20 July 1994

A fivemember independent committee submitted its report to the Government of India.

7 January 2002

MP offered cash compensation to the project-affected families as part of its rehabilitation and resettlement policy.

8 February 2002

The then PM,VP Singh, assured land compensation to the displaced.

14 April 2003

The Narmada Control Authority decided to raise the height of the Sardar Sarovar dam from 95 m to 100 m.

16 June 2005

The MP Government introduced the Special Rehabilitation Package where an oustee was offered cash to buy land of their choice.

23 February 2009

The Justice Jha Commission was directed by the MP High Court to probe issues of corruption in the rehabilitation and resettlement process.

24 June 2010

Justice Shah’s report, released in Bhopal, recommended rehabilitation of the displaced and environmental .protection

12 December 2014

NBA filed a petition in the Supreme Court against the Centre’s decision to increase the dam height by 17m.

Source: Narmada: 30 Years of Resilience

Translated from Hindi by Naushin Rehman

We Teach Life, Sir! – Jeevanshalas in the Narmada valley

Tags: Corruption, Increasing of the dam's height, Jantar Mantar, Resistance