The Indian Express, Feb 19 2016, Madhya Pradesh:  At Chikalda village in Madhya Pradesh, the Narmada flows quietly. It’s hard to gauge the river here — only the locals who dive in to collect coins thrown by devotees from the bridge nearby know its exact depth. This stretch of the river, said to be one of the spots where Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes were immersed, has witnessed many an agitation over a dam, the Sardar Sarovar, over 150 km away, in Kevadia colony of Gujarat. On February 8, the country’s apex court scripted what may well be the final chapter in a decades-old legal battle over the river and its waters.

At Chikalda village in Madhya Pradesh, the Narmada flows quietly. It’s hard to gauge the river here — only the locals who dive in to collect coins thrown by devotees from the bridge nearby know its exact depth. This stretch of the river, said to be one of the spots where Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes were immersed, has witnessed many an agitation over a dam, the Sardar Sarovar, over 150 km away, in Kevadia colony of Gujarat. On February 8, the country’s apex court scripted what may well be the final chapter in a decades-old legal battle over the river and its waters.

The Supreme Court directed the Centre and the Madhya Pradesh government to pay the final compensation of Rs 60 lakh to each of the 681 project-affected families which had refused the aid offered by the government. While giving the government two months to make the payment, the court set a deadline of July 31 for the families to vacate the area, failing which, the bench said, they would be evicted.

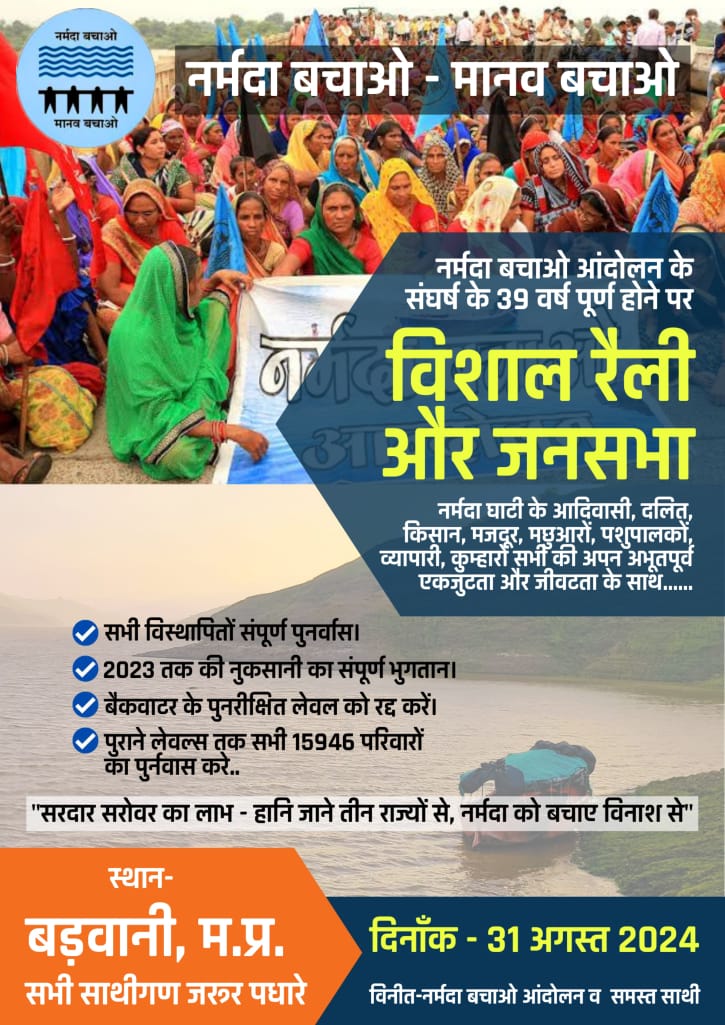

The court order paves the way for the Sardar Sarovar dam, among the most ambitious multi-purpose projects in the country, to be operated at full capacity. The Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), had, among other things, wanted the court to stop the government from using the dam to full capacity until all the project-affected were rehabilitated. While the Narmada Water Dispute Tribunal had in 1979 ruled that people affected by the project should be given land in return for what they stood to lose, the Madhya Pradesh government soon ran out of agricultural land it could offer. So far, only 239 people have got land in the state. More than a decade ago, the government drew up a financial package, the Special Rehabilitation Package (SRP), with the compensation to be paid in two installments.

While 3,366 families accepted the second and final installment — they are now out of the purview of the apex court ruling — 1,358 families accepted only the first installment but turned down the second. These families will now get Rs 15 lakh as ordered by the court.

It wasn’t easy to hold on, but Rukadiya Dhangar did — for over 30 years. The 47-year-old from Chikalda village in Badwani district and his family are among 681 in Madhya Pradesh who steadfastly refused any compensation in lieu of the land they stood to lose if the Narmada rose and swallowed their fields. Dhangar says he only wanted land in exchange for his four acres, where he grows wheat and maize; not the cash the government offered him.

One by one, people in Chikalda and those in neighbouring villages accepted, willingly or unwillingly, what the state government had to offer. Across the state, 3,366 people accepted the government’s financial compensation. For, what was certain was that some day, the river would rise and their fields would submerge. While some people got land and moved out of their homes, others took the money they got and bought land elsewhere.

A few kilometres before Chikalda, a village of 700-odd families on the banks of the Narmada, villagers talk about Dhangar, of how “lucky” he is. He is the only one in the village eligible for the Rs 60 lakh compensation; 15 others took the first installment but turned down the second — they now stand to get Rs 15 lakh.

Dhangar is glad he held on. “People in the village are jealous. They say I am lucky; it was no luck. Hamne himmat rakhke patak rakha (I showed courage and refused to give up the land),’’ Dhangar says. “It was not easy for me all this while. My family suffered because we had no money for my son’s treatment: he met with an accident and I had to spend Rs 4.5 lakh. There were times I wondered if I was doing the right thing… what if everyone accepted what was given to them and I would be left alone with my worries,’’ he says.

Through all these 30-odd years, as Dhangar travelled to Delhi and Bhopal, among other places, to take part in NBA-led agitations, he married, fathered four children — one son and three daughters — but “didn’t give up the fight”.

Though his “fight” was for alternative land — “Medhaji (NBA leader Medha Patkar) had said we should not settle for anything else” — the compensation of Rs 60 lakh was something he hadn’t expected. Though he is still waiting for details of the apex court judgment, he believes each of the five members of his family will get Rs 60 lakh. “Won’t we,” he asks.

His hut, which is off the main road, does not fall in the government-notified area that will be eventually submerged but his four-acre agriculture land in Gelgaon, a couple of kilometres away, will go under when the gates atop the dam in Gujarat are complete.

“Anyway, I am glad I waited. Now I will decide what to do once I get the money. Until then, I am not moving out of here,” he says.

Sitting inside her house in Chikalda village, Kalabai, 35, breaks down at the mention of her husband. “They came and took him away as if he was some criminal. They took away some papers from here and did not explain anything. I have no idea how my two children and I will survive this,’’ she says.

As villagers try to calm her, she says, “You won’t understand. Only a woman who has gone through something like this will know…’’

Over 45 days ago, her husband, Ramesh Solanki, 40, was arrested by the Badwani police for his alleged involvement in a fake registry scandal. The scandal, which first came to light in 2007, had farmers in Badwani, Khargone and Dhar districts allegedly colluding with brokers and government officials to strike land deals that existed only on paper. In order to get the second installment of the Special Rehabilitation Package, farmers had to buy land and produce registration papers as proof. But many allegedly produced fake documents and claimed the money.

Ramesh had taken the first installment of a little over Rs 2.80 lakh. The family of three brothers owned 7 acres in all and each adult male member was eligible to claim compensation. While his brothers bought nine acres, Ramesh didn’t. He claimed the second installment of around 2.79 lakh after allegedly producing fake registering papers for a plot of land he bought in Bagli, Dewas district.

Over six years ago, the government instituted a judicial inquiry into the scandal. The final report of the Justice S S Jha Commission is yet to become public.

Kalabai and her relatives claim brokers and government official cheated poor, illiterate farmers by getting them to put their thumb impressions on papers. Ramesh is now in Bagli jail in the state’s Dewas district. “I have not met him since they took him away. I don’t even have money to go there,’’ she says. She has one other regret. “He was hungry when the police came but they did not even let him have food.”

“I was in school when I first heard of the dam in Gujarat and how we could lose our land some day. But it was only some decades later, in 2001, when we received a notice saying that our land would be acquired, that it hit home,” says Tulsiram Yadav, standing in his field in Chikalda village.

The land he stands on —13 acres of the family-owned 16 acres — was acquired by the government in 2004. Back then, the two brothers got a little over Rs 13 lakh as compensation, which they used to buy 16 acres in Nanakbedi, a few kilometres away. “We put in some money of our own,” Yadav says. They also returned the residential plot they were given by the Narmada Valley Development Authority (NVDA) and invested the Rs 50,000 they received for it to buy more land.

He says he is glad he took the compensation. “I now grow crops on both my plots — the one in Chikalda and in Nanakbedi,” he says, adding that the family lives in Chikalda. Rules allow land owners to cultivate their original land until it is submerged. In some cases, land gets submerged only during the monsoon and farmers often go back to cultivate once the water recedes. While the family grows wheat on the Chikalda land, in Nanakbedi, they now grow sugarcane after a new sugar factory came up nearby a couple of years ago.

“I keep shuttling between the two plots because both require attention,’’ says Tulsiram, adding that one of his two sons helps him in the field; the other works for the state electricity board. He thinks he can do this for another five years, “maybe even more”. “I think it will take another five years before the dam reaches its full height. Until then, I will get to keep both my plots,’’ he says.

Sporing a big headgear and a bigger smile, Jahriya Mania Solanki says he doesn’t know how far he is from what had been his home for generations but now, he says, “this is home.” Five years ago, Jahriya, his wife and 10 children, along with the families of his four brothers, moved from their village Bhadal, in Badwani district, to Khalbujarg in the state’s Dhar district, where they got adjacent plots spread over 5 acres and where they now grow cotton.

“We don’t how how far we have travelled because we are all illiterate. All we know is that it’s a long way from here. We have to change three buses to reach the Narmada and then cross the river to go to the other side,’’ says Jahriya’s nephew Devji.

It was in 1998 that the government acquired the family’s 17-acre agricultural land in Bhadal village. “Dekhte dekhte hi dub gaya (the land submerged before our eyes),” says Jahriya’s younger brother Ohariya, talking of how they had been “hearing for at least 30 years” of how the river would one day consume their fields. While they waited for alternative land to be allocated, the family lived in a village nearby, till they got the land of their choice.

He says they were also offered land near Maheshwar in Khargone district. “But when we went with police and government officials, the villagers there attacked us. We later found out that some people had encroached on the plot that was meant for us. They started fighting and asked us to return,’’ recalls Jahriya, adding that it was only four years ago that they got this land in Khalbujarg, 90 km from Indore and 140 km from their home.

Talking of the SC order, Jahriya says, “We thank our stars that we got this land. An acre here costs around Rs 25 lakh. Our family wouldn’t have been able to buy 5 acres for Rs 60 lakh. Our next generations will do well in life.’’ He says though they are happy here, the family is yet to get the residential plots they are entitled to as part of the rehabilitation package.

“They did give us land to build homes, but that is five km from here and we turned it down. We have now asked for plots closer to our fields,” he says. The family – the four brothers and their families — now live in a makeshift house near their field. “Whatever it is, this is now home. We don’t get time to miss our old home. We are busy here,’’ says Devji, adding that they have bought a tractor, which they take turns to use.

Web: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/narmada-river-supreme-court-order-before-the-river-rises-after-a-decade-of-protests-some-have-move-on-some-stayed-behind-4532089/